Scorpion Ecology

Scorpion Distribution

Scorpions belong to the phylum Arthropoda, subphylum Chelicerata, class Arachnida, and order Scorpiones.

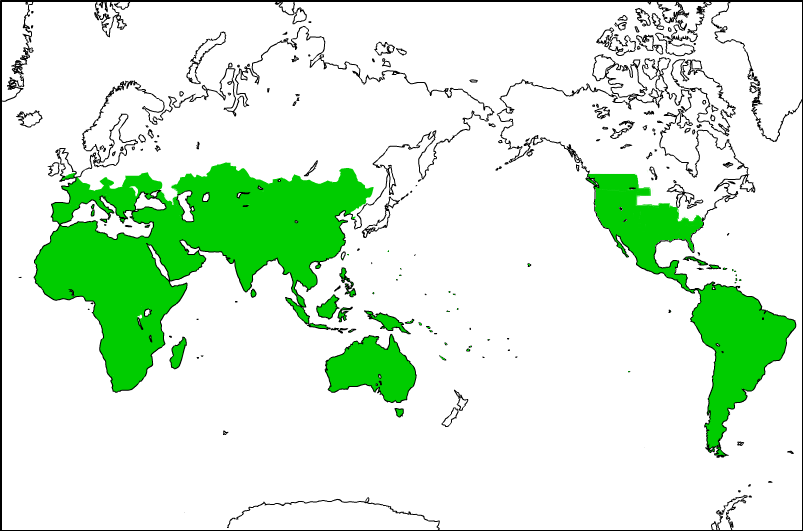

Fossil evidence indicates that scorpions date back to the Silurian period of the Paleozoic Era (approximately 438 million years ago) (Dunlop and Selden, 2013), suggesting they were among the earliest animal groups to successfully colonize land. It is believed that scorpions expanded their distribution before other animals fully ventured onto land. Currently, they are found on all continents except Antarctica (Fet et al., 2000).

In Japan, two species, the Australian Marbled Scorpion (Liocheles australasiae) and the Marbled Scorpion (Isometrus maculatus), inhabit the Sakishima Islands (Miyako Islands, Tarama Island, and Yaeyama Islands) on the western edge of Okinawa.

Scorpion Habitats

Scorpions are famously associated with deserts and tropical rainforests, but their actual habitats are diverse, including forests, grasslands, arboreal environments, coastlines and intertidal zones, high-altitude regions such as the Himalayas and Andes, and subterranean caves.

The highest altitude recorded for a scorpion discovery is 4,910 meters in the Peruvian Andes (Orobothriurus huascaran) (Ochoa et al., 2011), and the deepest underground is 916 meters in a cave in Southern Mexico (Alacran tartarus) (Francke, 2009).

Depending on the species, scorpions may conceal themselves in crevices in tree bark, cracks and gaps in rocks, or under fallen leaves, or they may live in burrows they dig in the ground. They are predators, feeding on other arthropods and small animals. In terms of activity patterns, some species are diurnal (active during the day), while others are nocturnal (active at night), with no reported commonality across major taxonomic groups (Warburg, 2013).

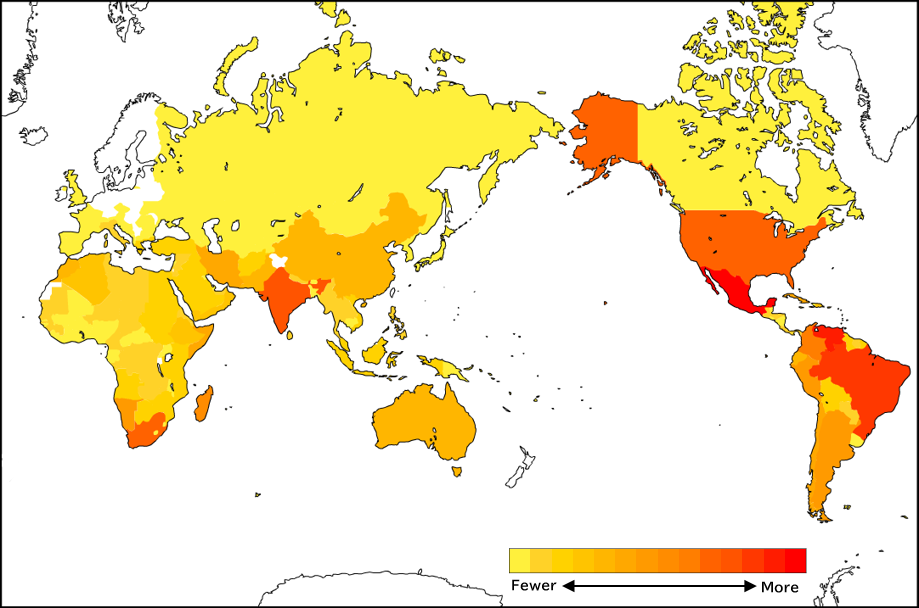

Although scorpions are often associated with potent venom, the strength of their venom is generally believed to correlate with the environment in which they live. Scorpions in tropical regions typically have slender metasomas (the tail segment) and weaker venom, but correspondingly larger pedipalps (the claw segment) with stronger grasping power. Conversely, scorpions inhabiting deserts and arid plains tend to have smaller pedipalps but relatively thicker metasomas and more potent venom.

|  | |

| Desert | Habitat | Tropical |

| Small | Pedipalps (Claws) | Large |

| Thick | Metasoma (Tail) | Slender |

| Strong | Venom Potency | Weak |

References ▼

- Dunlop, J.A., & Selden, P.A. (2013). Scorpion fragments from the Silurian of Powys, Wales. Arachnology, 16(1), 27-32.

- Fet, V., Sissom, W.D., Lowe, G., & Braunwalder, M.E. (2000). Catalog of the Scorpions of the World (1758-1998). New York Entomological Society.

- Ochoa, J.A., Ojanguren Affilastro, A.A., Mattoni, C.I., & Prendini, L. (2011). Systematic revision of the Andean scorpion genus Orobothriurus Maury, 1976 (Bothriuridae), with discussion of the altitude record for scorpions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 359, 1-90.

- Francke, O.F. (2009). A new species of Alacran (Scorpiones: Typhlochactidae) from a cave in Oaxaca, Mexico. Zootaxa, 2222, 46-56.

- Warburg, M.R. (2013). The locomotory rhythmic activity in scorpions: With a review. Arthropods, 2(3), 95-104.